Sometimes when story time was running out, and she was nearing the end of a chapter, Mrs. Mertzweiler would ask for a show of hands: “Who wants to extend story time today?” Other times she might encourage us, “If everyone can finish their math work today, maybe we’ll be able to read two chapters from Charlotte’s Web!”

I was fascinated with Charles Schultz’s Peanuts when I was eight years old. I was building a library of Peanuts comic books—not the popular magazine-style comics with glossy covers, but the paperback book format I could get at Walgreen’s. I would finish one and then walk the four blocks past Byerly’s to the drug store with two quarters and two pennies for another. When Mrs. Merzweiler discovered that I had several of the books tucked inside my desk, she encouraged me to quietly read them if I had finished an assignment early. Before long, with her encouragement, I was lending Peanuts books out to classmates. If someone had extra time available while the rest of the class was finishing an assignment, if they were fidgeting or talking aloud, Mrs. M would ask if I would share one of my Peanuts books. Soon everyone was working to finish their assignments so they could have some comic book reading time. I created a hand-written library ledger with the title of each book written on a separate line and the name of the student who borrowed it.

This is how Rob Lear and I became friends. Rob was good at drawing, and he would borrow comic books from me and use them to practice drawing Peanuts characters. Kids could tell Rob which was their favorite character, and Rob would make a pretty good drawing for them to keep. Sometimes I would get books back and find a sheet of paper folded into the back with one of Rob’s drawings of Snoopy or Woodstock. Rob showed me how to do some simple drawings of my own—more stick figures and two-dimensional fighter jet action doodles than anything as sophisticated as Rob could do, like Lucy yanking a football away as Charlie Brown flipped backward trying to kick it.

Mrs. M had to balance her rewards for timely assignment completion with discouragement of hasty, sloppy, or incomplete work. Most of us would rather have read comic books than work through pages of arithmetic exercises. But it wasn’t acceptable to race through the assignments just to resume reading a Peanuts comic. We had to ask permission. We would present our work to Mrs. M for evaluation, and, if she agreed the assignment had been completed satisfactorily, we could spend any remaining time reading or drawing. I was a slow learner in this regard. I would confidently rip through my addition or subtraction tables, scribbling the sums below the total lines, then race the sheets up to Mrs. M’s desk like late-breaking news alerts. She would look at them carefully and, as often as not, send me back to work on them some more, sometimes just to write my answers down more carefully so that she could decipher them. I would power-walk back to my desk, erase the answers I’d written, and painstakingly draw the same figures, making sure the numerals each looked right. She would look them over again, and this time she might even find an error in my calculations somewhere and point out to me that she could see from my erasure marks that I had gotten it right the first time but copied it down incorrectly the second time. She told me she knew I wanted to finish quickly, but that by going so fast and making silly mistakes, I was actually taking more time getting things done.

One day, after we had finished taking a spelling quiz of words we had been studying all week, Mrs. Merzweiler called me to her desk. At her desk, she pointed out the spelling mistakes I’d made.

I got most of them right—pretty good, I thought.

She produced another of my quiz papers from earlier in the week—the same dozen words. On that prior day I had gotten all the words right. “You know how to spell these words,” she said. “I think you’re just having a little more trouble being patient and checking over your work today.”

I nodded.

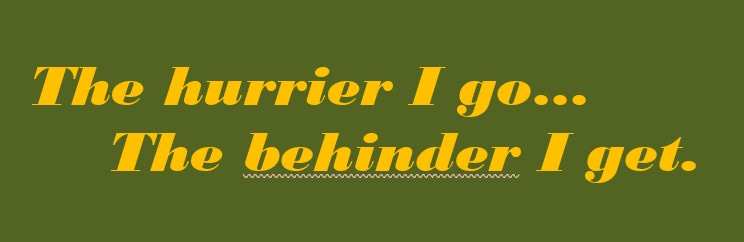

Then she showed me a poster she had hung at the front of the classroom, just behind her desk. I hadn’t noticed it before. It was a big glossy poster like you could buy in a record store, a photograph of a beautiful tortoise crawling across leaves and bark mulch near the base of a big tree. The message on the poster was in burnt-yellow letters in the scripty font so popular in the late Sixties:

“I saw this in a store the other day,” Mrs. Mertzweiler said, “and it made me think of you.”

I smiled. I liked hearing that she thought of me sometimes even when she wasn’t in our classroom. “Is ‘hurrier’ a real word?” I asked.

“I don’t think so, but you know what it means just the same, don’t you?”

I nodded.

She smiled and sent me to my desk.

After that, rather than point out every mistake or error I made, she would occasionally call my name to get my attention, and then point over her shoulder to the tortoise poster. I might be standing up before everyone else to bring a completed assignment to her desk, but before I’d take my first step she would catch my eye, raise her eyebrows a little, and point at the tortoise. I would halt, look at the paper in my hands, then sit down again to check over my work.

Mrs. M was going to have a baby. Sex education wasn’t part of the regular second-grade curriculum, but that didn’t stop Mrs. M from talking comfortably and frankly about her pregnancy and what that meant. We learned a lot. She said that the baby was expected to arrive late in the spring, very close to the end of our school year. She said that she was going to try very hard to not miss school days, but we might need to have a substitute teacher sometimes, and she might not even be able to stay the full year.

There were a few days in the spring when we arrived to find a stranger sitting behind Mrs. M’s desk. Every morning when I got off the bus and walked into school, I was hoping that Mrs. Merzweiler would be there, and almost always she was. My concern grew greater as we got closer to the last day of school. On the morning of the last day of school I was afraid that maybe I wouldn’t be able to see her and say goodbye before summer vacation. Happily, she was there, and we had a particularly nice last day. At the end we had some spare time before the busses came. Mrs. M asked each of us to tell the class something fun or exciting we were planning for the summer. She went first: She was going to finally have her baby and spend the summer learning to be a mommy, something very new and exciting for her.

After we had all finished and the busses were waiting and everyone was rushing to the door—summer at last!—Mrs. M asked if I would please come to her desk. I felt a little nervous and sad—I didn’t want my last conversation with Mrs. Merzweiler to be about something I might have done wrong. I was also eager to get going.

“Steven, I want you to have this,” she said. She was taking the tortoise poster off of the wall.

I’m certain I was beaming.

“And I want you to ask your mother to help you put it up on the wall in your bedroom where you’ll be able to see it, all right?”

I said that I would. I took the rolled-up poster from her, and I was already thinking about how I would have to protect it on the bus ride home so that it wouldn’t get crunched. “Thank you,” I said.

Mrs. Merzweiler smiled and pulled me close. I wrapped my arms around her neck, buried my face in her hair for a moment, sad with the goodbye and also happy to have a gift from her to help remember.