“Lemme tell you a story. I could write a book.”

I’m mixing two black Russians—it’s nearly always happy hour here, and I saw him coming. I don’t recall his name, but I remember what he drinks. Six other patrons in the bar—a pair of threes. It’s a good story, I hope, ‘cause I’ve been making the best of a slow Sunday night. There’s a lot I’ve been trying to put down in this journal.

He's lonely. He comes in, corners anybody too polite to make him shove off. He wags his chubby fingers over his black Russians and talks about his CPA business and his church and all the different people he prays with and his cars and his lakeshore property and that time years ago when he took the Chinese guy named Tony who used to own this joint I’m working in now over to the Lamplighter to put dollar bills in the girls' panties. I remember everything about this guy except how he tipped me last time he came in. I remember how tired my feet get sometimes.

“Right with you.” I put the Kahlua bottle away.

“Okay, Joe.”

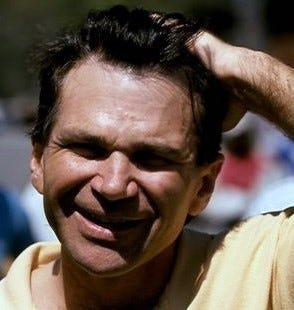

He calls me Joe because he thinks I look like Joe Isuzu, the TV pitch man for Isuzu Trucks. Thing is, he’s right. If I shaved my beard off, Joe Isuzu is what I’d look like.

So, I set his drinks down and look around to see if anyone (please!) needs a drink.

The girls, as I call them, are sitting at a table, the two sisters on either side of the friend who joined them tonight, retelling stories of their deceased husbands. Brandy-water, vodka-sour, gin & tonic. They’re each on their fourth and they only planned on one more each after that first two-for-one, but there’s so much to talk about, they’ve found they have so much in common—the two who are sisters—that every day they are amazed anew at why they never liked each other when they were younger. Their glasses are full, but the ice is nearly gone. I don’t know whether it’s because they feel obligated to have drinks in their hands as long as they’re in here or whether it’s because they can’t figure out whose turn it is to count out the crumpled dollar bills and dimes and nickels from their darling coin purses to make up the six dollars and seventy-five cents for another round, but none of them wants to be the first to finish her drink.

Cy and Donny and Billy are at the other end of the bar, nearer the station where I mixed this guy’s drinks. They’ve been here about four hours, and they’ve slowed down. They have fresh drinks, so no help from them.

I have all my dish racks, so the kid Alan hired to wash dishes won’t be bringing glassware to put away. The fruit’s all cut up—I can’t even pretend about having to spear some olives while I listen to this guy’s story.

“Lemme tell ya, Joe,” he says. He looks as if Ed Asner gained 120 pounds and plopped onto a stool at the Chopstick Inn to have a few. “At my church, we’re in our fifty-third consecutive week of prayer. I’m the committee chairman, so I’m in charge of scheduling fourteen other people. We pray in shifts. It’s mostly men. We just have to be there to pray for a couple of hours each day. There are women, too, but I don’t schedule them to pray alone.

“So, this one young lady, twenty-five or so I guess, maybe about your age, I pray with her once or twice a week, and the other night in the parking lot she tells me she’ll have to miss our prayer session on February fifth. ‘That's fine,’ I tell her, ‘but how come?’ I ask. ‘I’m getting married,’ she tells me. ‘That’s wonderful!’ I say. ‘Where?’ I ask, ‘cause I know it isn’t in our church on February fifth. ‘Las Vegas,’ she says. ‘Las Vegas? Why all the way out there?’ ‘Well,’ she says, ‘he isn’t Catholic.’

“Well, Joe, I can't say much. She’s young, and she has to make her own choices. I can’t tell her what to do, but I don’t know I’d make that choice, to go off to Las Vegas and marry someone who’s not a Catholic. But that isn’t all of it, Joe! Then she tells me she’s pregnant too, and I’m a little surprised. But she’s a nice girl—I pray with her every week and all. ‘But it isn’t his, Bob!’ she says. So, she’s marrying this guy, and she’s pregnant already, and it isn’t even his baby. But the reason they’re going to Las Vegas, she tells me, is because they’ve arranged to sell her baby when it’s born, and they have to meet the people who are buying it. Women gotta make their own choices, ya know what I’m sayin’ Joe?”

“They sure do.”

“I mean, I don’t want to have to tell anyone what to do, I can’t make choices for women, but I could never. I mean if it was my baby, I could never. Sell it, give it away, kill it or nothin’. If it was my baby, I’d love it and raise it and bring it up to be able to, to, to—” he taps his chest with his fists, a piece of moist popcorn hanging off the corner of his meaty lip.

“Make choices.”

“Yeah. To make choices. You understand, don’t you, Joe.”

I shrug. I do understand, though. I’m standing here listening to Bob. I should be home with Beth and Dane and The Fetus. But I don’t mention my pregnant wife to Bob, because it isn’t about me here at The Chopstick Inn, it’s about Bob, even though to him I’m just the bartender, the one who looks like Joe Isuzu.

He gulps down the last half of his second black Russian. “I guess I’ll have a couple more.”

I’m icing rocks glasses and he asks, “Can I be an asshole?”

“How’s that?”

“Can I be an asshole and ask you to get more popcorn for me?”

I smile, deliver his drinks, go across the room to the popcorn machine. I remember he likes salt, but not too much.

“Ten thousand dollars. She said they need it for a down payment. Believe that, Joe? She’s sellin’ her baby. To buy a house.” He takes a handful of popcorn. “Thanks, Joe.”

And no one else comes into the bar and Cy and Donny and Billy and the girls are drinking slow—I don’t know if they’ll have any more. I need better shoes. I stand in my cheap shoes keeping eye contact with Bob because I can’t even pretend that I have something else I have to do. Where are Vic and Sylvia? Sylvia could talk with this guy. If I locked this guy in a room with Sylvia, half an hour and they would either discover they’re soul mates or machine-gun each other. Vic wouldn’t be having any of it. Maybe out in the parking lot Vic saw Bob walking in, so he took Sylvia across the street to Ted’s Bar instead.

My mind’s been wandering and he’s wagging his sausage finger at me over empty rocks glasses, asking for another pair of drinks. He told me some other night that seven was his limit. He knows he gets sloppy after seven. (I’d say he’s plenty sloppy after four.) I’m wondering whether he’ll quit after these next two or push right to his limit.

Time crawls. Nobody else arrives. Bob discovers we both drive 1985 four-cylinder Chevy Celebrities, and he decides to have one more. “Still happy hour, Joe?”

I scan the room. The girls are readying themselves for home. The squat one—the one whose reddish hair cloud is ratted wide and whose maroon stretch pants are fully stretched—just rounded the corner returning from the ladies’ room and bumped into a cocktail table near her own. The sisters are standing, each holding a jacket up and inspecting it to be sure it’s her own. Billy and Cy’s glasses are low, and they’re looking alive again. Together they’ve sided against Donny on a matter of sports trivia. I just made two for Donny, so I won’t be able to refuse them a two-for-one if they ask in a minute, so to Bob I must say “Yes.”

“Well, what the hell, Joe. Do me up another pair.”

“You want both?”

“What the hell. Go for it.”

“I thought seven was your limit.”

“I don’t work tomorrow, and no plans. I’m having my fun tonight. You're all right, Joe.”

“How ‘bout if I make one, and make the other when you finish the first, so the ice doesn’t melt too fast.”

“I don’t care, Joe. Just gimme ‘em both.”

I ice two glasses and pour vodka and Kahlua. I’m reaching for the filberts when he says, “On second thought, just make me one, Joe.”

“Okay.” I dump one of the drinks, look over at Donny, and Donny rolls his eyes: Who is this guy?

Bob wants to tell me about a new commercial for Diet Coke or Diet Pepsi with Ray Charles. I can’t tell from his description whether Ray is selling Coke or Pepsi, and he’s frustrated that I’m not following. It would help if he could find the occasional verb.

“Black guy, blind, wrong stuff. Pepsi, mistake, should Diet. Coke!” He is being entirely supported by his barstool now. His head rests squarely atop his shoulders with no evidence of a neck. His black Russian balances on his belly, steadied by two thick fingers. “See?”

“Sure—Ray Charles is doing a blind taste test for Diet Coke or Diet Pepsi—”

“Pepsi.”

“Right, Diet Pepsi, and it’s not a good commercial because you know it was scripted.”

“Right. Money.” He rubs the two fingers that were steadying his drink together, nods with his eyes closed tight. “Vodka in the can, all ye know.”

“Right.”

“You're okay, Joe.”

“Thanks.”

“I know you're not really Joe Isuzu. I just call you that. Tryna be funny.”

“It’s all right.”

“I gotta go, Joe.”

“Okay. Take it easy.”

Six dollars and change are still on the bar.

“I’m divorced, you know.” He rolls off his stool, looks for his jacket. He’s wearing it.

“You mentioned.”

“Yup. Here, Joe. This is for you.” He picks up the six dollars, a five and a one, holds them out, the five folded back. I take the one, he pockets the five. He swipes at the change, misses a quarter and a dime.

When he’s gone, I collect the empty glass, popcorn basket, two coins, wipe the bar down.

I enjoyed this one too! You’re right, or should I say “Bob” is right, you do look a bit like Joe Isuzu! 😂 Great job describing the people in the bar. I felt like I was right there with you. I happen to be taking a break on the couch with my feet up, so my feet don’t hurt.

You must have a lot of interesting stories to tell from your years of bartending. Keep on writing!